This blog sifts books, poems, and zines--mining their contents for ideas, inspiration, exercises, and insights into the writing craft. It is also the home site of author Thomas Maltman, who writes, teaches, and keeps busy raising three daughters here in the Twin Cities.

Monday, November 9, 2009

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Worth the Price of Admission

Before bedtime, pick up the alarm clock. Set it to ring two hours earlier than your usual wake-up time.

There are many other worthy chapters in this essay collection. For teachers of writing, chapters like Crystal Wilkinson's "Birth of a Story in an Hour or Less" make Now Write! well worth the price of admission.

Saturday, August 1, 2009

Book Lovers Night at the College of Saint Benedict's!

I am very excited about this upcoming event. I'm heading to the College of Saint Benedict's as part of the summer reading program next week. I look forward to the evening and conversation!

SB “Book Lovers' Night" features author Thomas Maltman

07/27/2009

Thomas Maltman, author of The Night Birds, is the featured guest at the College of Saint Benedict’s “Book Lovers' Night” Wednesday, Aug. 5 at Teresa Reception Center, Main Building, CSB.

Thomas Maltman, author of The Night Birds, is the featured guest at the College of Saint Benedict’s “Book Lovers' Night” Wednesday, Aug. 5 at Teresa Reception Center, Main Building, CSB.

The book program begins at 6:45 p.m., and is free to the public. An optional “light” dinner will be offered at 6 p.m. for $7.

The Night Birds is Maltman’s first novel and was released in 2007 by Soho Press. Set in 1876 in Minnesota, the book spotlights 14-year-old Asa Senger and his German immigrant family. It is a time of uncertainty for the family, as vast clouds of locust descend on the Great Plains. The James-Younger gang, a band of murderous thieves, is rumored to be riding north of the area.

During this time of uncertainty for Asa and his family, his Aunt Hazel arrives on the scene. Confined for years in an asylum, she brings with her stories of the Dakota War (also known as the Dakota Conflict) of 1862. Her arrival propels the story into the past, as far back as the Senger family’s initial settlement in slave-holding Missouri.

The Night Birds has received the Alex Award from the American Library Association, the Friends of American Writers Literary Award and the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America.

"We all set our sights on the Great American Novel. . . . (Maltman) comes impressively close to laying his hands on the grail," wrote reviewer Madison Smartt Bell in The Boston Globe newspaper.

Maltman’s essays, poetry and fiction have been published in the Georgetown Review, Great River Reviewand Main Channel Voices, among other journals. Maltman, who lives in Minneapolis, is expected to release a second novel, Little Wolves, soon.

The Night Birds will be on sale at 20 percent off at both the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University bookstores through the event. For more information on the event, please call 320-363-2119, or e-mail bookevents@csbsju.edu.

Diane Hageman |

Monday, July 27, 2009

Burn Calories - wikiHow

Burn Calories - wikiHow

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

Rules for Writing a Novel?

One of those guides that I've written about in my Goodreads account is Sol Stein's How to Grow a Novel. Stein is a former agent and author and provides an insider's view of the art. (He's also the author of Stein on Writing, and The Magician.) He places a writer's focus where it should be, on the reader. In the appendix section he offers some "principles" that I'd like to list here for those of you spending your summer writing. I'm a lover of lists and I find this one instructive. For copyright reasons this is just a partial sampling of the book. The list itself does not hint at the full riches the book offers. For that you'll need to buy yourself a copy!

Before Beginning to Write

- What does your protagonist want badly?

- Who or what is in your protagonist's way? ("Who" will be more dramatic)

- Get into the skin of characters who are different from you.

- Why would you want to spend time in the company of the person you are choosing as your protagonist?

- How do your characters view each other? Write a short paragraph about each character's views of the virtues, faults, and follies of other important characters. Save these paragraphs for referral and guidance.

- How are you planning to hook your reader on page one?

- Consider starting a with a scene that is already underway.

- What are the dramatic conflicts you intend to let the reader see in each chapter?

Keep in Mind While Writing

- The "engine" of your story needs to be turned on as close to the beginning as possible. The "engine" is the point at which a story involves a reader, the place at which the reader can't stop reading.

- Keep the action visible on stage as much as you can.

- Don't mark time; move the story relentlessly

- Is your hero or heroine actively doing something rather than being done to?

- Use surprise (such as an unexpected obstacle) to create suspense.

- During your descriptions of places do you also move the story along?

- End scenes and chapters with thrusters that make the reader curious about what happens next.

- To increase a reader's interest, deprive him of something he wants to know.

There are many items on this list (25 in all!) and I recommend you buy the book which includes many instructive examples highlighting why each point is so crucial. Copyright:

Stein, Sol. How To Grow a Novel: The Most Common Mistakes Writers Make and How to Avoid Them. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1993.

Saturday, March 7, 2009

April 2008

By Tad Simons

When it comes to lynchings, Minnesota does not have a stellar record. More than a few times in our state’s history people have opted for the expedience of the rope over the plodding rule of law, and each time it has happened, whether the motive was to hang a few black men or rid the prairie of Indians, a wave of shame and guilt has rippled through Minnesota’s collective conscience.

Minnesotans are good people by and large, not given to bursts of vengeance, but these tragedies are part of our legacy, and though we might wish otherwise, all of us share the responsibility for making sure such things never happen again. One of the ways we do this is by continuing to tell the stories of these unfortunate events; or, as two Minnesota– bred authors have done in their new books (one fiction, the other nonfiction), tell the story behind the story.

Sunday, March 1, 2009

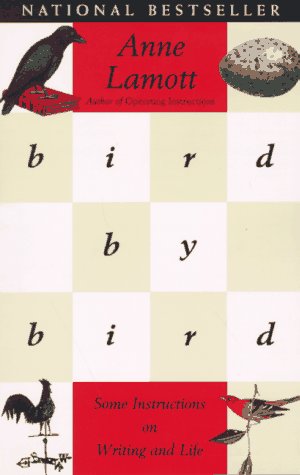

I am always on the hunt for good books on writing so I gave this one a try based on the recommendation of a good friend. I liked it so much I assigned the book for my fiction workshop last fall and I'm glad to report that students responded well to it, too. I've included some of my favorite quotes below, along with my comments in italics.

Quotes from Anne Lamott's Bird by Bird

“Publication is not all it’s cracked up to be. But writing is. Writing has so much to give, so much to teach, so many surprises. That thing you had to force yourself to do—the actual act of writing—turns out to be the best part.”

Writing is a lonely business filled with rejection slips and disappointment. For most of us, it just won't pay the bills. Publication does matter, however, but Lamott is right in pointing out that there's more to strive for. We should try to make art with our writing, something lasting and true. We should savor those rare successes, a publication, an award, but the key thing is to keep up with the daily struggle of writing and growing in our craft.

Getting Started

“The very first thing I tell my new students on the first day of a workshop is that good writing is about telling the truth” (3).

“But after a few days at the desk, telling the truth in an interesting way turns out to be about as easy and pleasurable as bathing a cat. Some lose faith” (3).

“Flannery O’ Connor said that anyone who survived childhood has enough material to write for the rest of his or her life” (qtd in Lamott 4).”

“You sit down, I say. You try to sit down at approximately the same time every day. This is how you train your unconscious to kick in for you creatively” (6).

I love the Flannery O'Connor quote. I recently had my students complete an activity where they draw the floorplan of the first house they remember living in--an activity inspired by Janet Burroway's great introductory text Imaginative Writing. Once the floorplan is complete they trace the map with their fingers, marking places of special significance. The bathroom mirror where they invoked "Bloody Mary." The spot on the white carpet where they spilled kool-aid. It's always surprising to hear the memories that rise to the surface. We then talk about the O'Connor quote and how each of us has experienced the requisite emotions--sadness, joy, betrayal--the raw working material of good fiction.

Daily Work

“What’s real is that if you do your scales every day, if you slowly try harder and harder pieces, if you listen to great musicians play music you love, you’ll get better” (14).

“It reminds me that all I have to do to is write down as much as I can see through a one-inch picture frame…just one paragraph describing this woman, in the town where I grew up, the first time we encounter her” (18). “E.L. Doctorow once said that ‘writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way” (qtd in Lamott 18).

I love the idea of the frame. Not everyone can write Stephen King style--2000 words a day. For busy parents, for those who teach, Lamott's idea of a frame is more practical.

First Drafts

“Now practically even better news than that of short assignments is the idea of shitty first drafts. All good writers write them. This is how they end up with good second drafts and terrific third drafts” (21).

“Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor, the enemy of the people” (28).

“I think that something similar happens with our psychic muscles. They cramp around our wounds—the pain from our childhood, the losses and disappointments of adulthood, the humiliations suffered in both—to keep us from getting hurt in the same place again, to keep foreign substances out” (30).

“Kurt Vonnegut said, ‘When I write, I feel like an armless, legless man with a crayon in his mouth’” (qtd in Lamott 32).

“Writing a first draft is very much like watching a Polaroid develop. You can’t—and, in fact, you’re not supposed to—know exactly what the picture is supposed to look like until it has finished developing” (39).

On Character Shaping

“And finally as the picture comes into focus, you begin to notice all the props surrounding these people, and you begin to understand how props define us and comfort us, and show us what we value and what we need and who we think we are” (40).

“Knowledge of your characters also emerges the way a Polaroid develops: it takes time for you to know them. One image that helps me begin to know the people in my fiction is something a friend once told me. She said that every single one of us at birth is given an emotional acre all our own […] One of the things you want to discover as you start out is what each person’s acre looks like. What is the person growing, and what sort of shape is the land in” (44-45)?

“Go into each of these people and try to capture how each one feels, thinks, talks, survives” (46).

“One line of dialogue that rings true reveals character in a way that pages of description can’t” (47).

“Someone once said to me, ‘I am trying to stay in the now—not the last now, not the next now, this now. Which ‘now’ do your characters dwell in” (48)?

On Hope

“In general, there’s no point in writing hopeless novels. We all know we’re going to die; what’s important is the kind of men and women we are in the face of this” (51).

Plotting Your Work

“Plot grows out of character. If you focus on who the people in your story are, if you sit and write about two people you know and are getting to know better day by day, something is bound to happen” (54).

“Drama is the way of holding the reader’s attention. The basic formula for drama is set-up, buildup, payoff—just like a joke…Drama must move forward and upward, or the seats on which the audience is sitting will become very hard and uncomfortable…The climax is that major event, usually toward the end, that brings all the tunes you have been playing so far into one major chord, after which at least one of your people is profoundly changed” (59-61).

“…which goes ABCDE, for Action, Background, Development, Climax, and Ending. You begin with action that is compelling enough to draw us in, make us want to know more. Background is where you let us see and know who these people are, how they’ve come to be together, what is going on before the opening of the story. Then you develop these people, so that we learn what they most care about. The plot—the drama, the actions, the tension—will grow out of that. You move them along until everything comes together in the climax, after which things are different in some real way. And then there is the ending: what is our sense of who these people are now, what are they left with, what happened, and what did it mean” (62)?